Tinkering by the Book

For 15 years, I was the lead instructor for a SEED program, funded by USAID. Cohorts of 20 teachers from rural areas were chosen by their Latin American governments to study in the USA for a year and then return to be change agents in their communities and countries.

Many of these teachers/maestros in this program did not have electricity, paper, potable water, etc. in their communities. But how could the maestros help their kids read and write if they had no books?

Since we were a “strengths-‐based” program, we helped the maestros inventory and work with what they did have—recycled and simple materials, beautiful environments, incredible cultures, and personal creativity. We began by helping them write their own books—to begin libraries.

Each maestro (teacher) chose an important time in his life to draft into a story that would be made into a book. We encouraged them to recall the growing up years and think of stories they would like to share with their students.

They read their drafts to each other and we all told what we liked best about each story. This was an especially touching experience and many of us cried a little as we read or listened. Different teachers had experienced floods, mudslides, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, wars, deaths and even genocide. In the midst of these many had found a mission, a meaning, a solidarity, a will to overcome. Mixed with these were charming tales of mischievous, curious, and adventurous children exploring their lives.

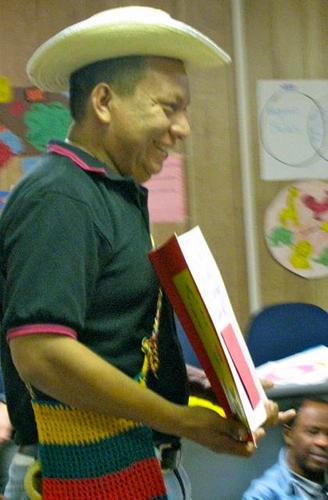

To elaborate their stories, we turned each maestro into a director and had them use their colleagues as actors to dramatize the stories they had written. Props, costumes and so on were improvised. After a few years we began to videotape these as well.

For the illustrations, my colleague asked each maestro to choose one thing they wanted to illustrate in their book and to draw, paint, and create it over and over in different media—markers, crayons, paints, Styrofoam prints, black ink, etc. She then helped them chose the style that seemed strongest for them. Each maestro (not artists!) illustrated their own book.

Finally, they created covers and sewed together their books.

We gave groups of maestros a temporary classroom with cardboard boxes, newspaper and butcher paper, with which to create an interactive library. They used their personal story books to stock the libraries, plus these other original books they created over the year:

• “big books,” in which they re-‐told and illustrated traditional tales from their cultures.

• pop-‐ups and other little books on topics like strategies for dealing with bad feelings.

• haikus, songs and poems on everything from trees to water to prime numbers to

alliteration.

• booklets created for parents on topics such as dyslexia, stress, drug abuse and other

topics.

They hosted open houses for their libraries, shared their books at national and international conferences, and read their books (with accompanying activities) to other teachers and children. Finally, they took their books home and shared them with their own students, whom they helped to create their own books, too.

I still keep in touch through social media with many of the hundreds of maestros with whom I worked. Most are now doing their own tinkering with teaching their kids to read and write, to think and to value themselves and their worlds. My hope is that they will always cherish the boundless creativity within themselves and their students.